Is There a Humanist Style of Art Through History

Peter Paul Rubens, three paintings from the 24-picture bike Rubens painted for the Medici Gallery in the Grand duchy of luxembourg Palace, Paris (today in the Musée du Louvre, Paris), 1621-25, oil on canvas. From left to right: The Presentation of the Portrait of Marie de' Medici, The Hymeneals by Proxy of Marie de' Medici to King Henry IV, Arrival (or Disembarkation) of Marie de Medici at Marseilles(photo: Steven Zucker, CC By-NC-SA 2.0)

Art history might seem like a relatively straightforward concept: "fine art" and "history" are subjects most of us first studied in elementary schoolhouse. In practice, nevertheless, the idea of "the history of art" raises complex questions. What exactly exercise we mean by art, and what kind of history (or histories) should we explore? Let'due south consider each term further.

Art versus artifact

The word "art" is derived from the Latin ars, which originally meant "skill" or "craft." These meanings are yet primary in other English language words derived from ars, such as "artifact" (a thing made by human being skill) and "artisan" (a person skilled at making things). The meanings of "art" and "artist," however, are not so straightforward. We understand fine art as involving more than only skilled adroitness. What exactly distinguishes a work of fine art from an artifact, or an artist from an artisan?

When asked this question, students typically come up up with several ideas. One is beauty. Much art is visually striking, and in the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries, the analysis of aesthetic qualities was indeed central in art history. During this time, art that imitated aboriginal Greek and Roman art (the art of classical antiquity), was considered to embody a timeless perfection. Art historians focused on the so-called fine arts—painting, sculpture, and compages—analyzing the virtues of their forms. Over the past century and a one-half, still, both art and art history have evolved radically.

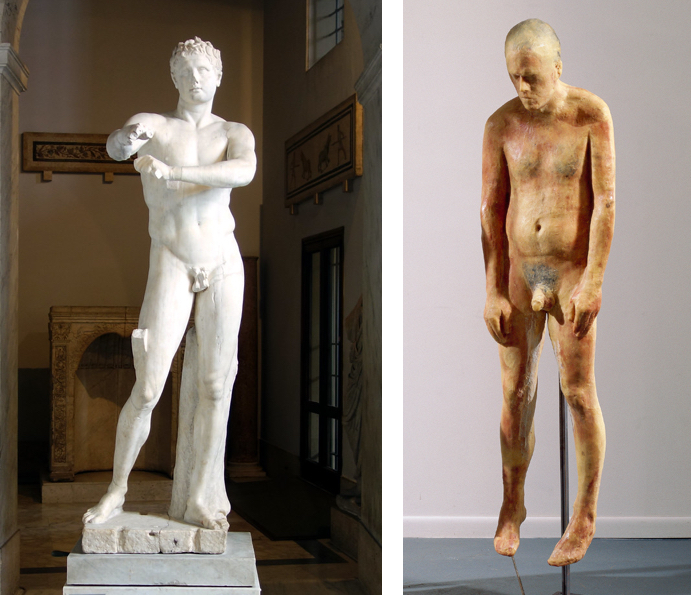

Left: Lysippos, Apoxyomenos (Scraper), Roman re-create later on a bronze statue from c. 330 B.C.East., six′ nine″ high (Vatican Museums); right: Kiki Smith, male figure from Untitled, 1990, 198.1 × 181.6 × 54 cm, beeswax and microcrystalline wax figures on metal stands (Whitney Museum of American Art)

Artists turned away from the classical tradition, embracing new media and aesthetic ideals, and art historians shifted their focus from the analysis of art's formal dazzler to interpretation of its cultural meaning. Today nosotros sympathise beauty equally subjective—a cultural construct that varies beyond time and infinite. While nearly art continues to exist primarily visual, and visual analysis is still a key tool used by fine art historians, beauty itself is no longer considered an essential attribute of art.

A second common answer to the question of what distinguishes art emphasizes originality, inventiveness, and imagination. This reflects a modern understanding of art as a manifestation of the ingenuity of the artist. This idea, even so, originated v hundred years ago in Renaissance Europe, and is non straight applicable to many of the works studied by art historians. For example, in the case of ancient Egyptian art or Byzantine icons, the preservation of tradition was more valued than innovation. While the idea of ingenuity is certainly important in the history of art, it is non a universal aspect of the works studied by art historians.

All this might atomic number 82 one to conclude that definitions of art, similar those of beauty, are subjective and unstable. One solution to this dilemma is to propose that art is distinguished primarily by its visual agency, that is, by its ability to captivate viewers. Artifacts may be interesting, but art, I propose, has the potential to motion the states—emotionally, intellectually, or otherwise. Information technology may do this through its visual characteristics (calibration, composition, colour, etc.), expression of ideas, adroitness, ingenuity, rarity, or some combination of these or other qualities. How art engages varies, just in some manner, art takes usa beyond the everyday and ordinary experience. The greatest examples attest to the extremes of human ambition, skill, imagination, perception, and feeling. As such, art prompts the states to reflect on fundamental aspects of what it is to be human. Any artifact, as a product of human skill, might provide insight into the homo status. Only fine art, in moving beyond the commonplace, has the potential to practise then in more profound ways. Fine art, then, is perhaps best understood equally a special class of antiquity, infrequent in its ability to brand usa call back and feel through visual experience.

Coatlicue, c. 1500, Mexica (Aztec), found on the SE edge of the Plaza Mayor/Zocalo in Mexico City, basalt, 257 cm high (National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC Past-NC-SA 2.0)

History: Making Sense of the Past

Similar definitions of art and beauty, ideas about history have changed over time. It might seem that writing history should be straightforward—it's all based on facts, isn't information technology? In theory, yes, simply the evidence surviving from the past is vast, bitty, and messy. Historians must make decisions virtually what to include and exclude, how to organize the material, and what to say about it. In doing so, they create narratives that explain the by in means that brand sense in the present. Inevitably, every bit the nowadays changes, these narratives are updated, rewritten, or discarded altogether and replaced with new ones. All history, so, is subjective—as much a production of the fourth dimension and place it was written every bit of the show from the past that it interprets.

The discipline of fine art history developed in Europe during the colonial period (roughly the 15th to the mid-20th century). Early fine art historians emphasized the European tradition, jubilant its Greek and Roman origins and the ideals of academic art. By the mid-20th century, a standard narrative for "Western art" was established that traced its development from the prehistoric, aboriginal, and medieval Mediterranean to mod Europe and the U.s.a.. Art from the rest of the world, labeled "non-Western art," was typically treated simply marginally and from a colonialist perspective.

The immense sociocultural changes that took place in the 20th century led art historians to amend these narratives. Accounts of Western art that once featured simply white males were revised to include artists of colour and women. The traditional focus on painting, sculpture, and architecture was expanded to include so-called minor arts such as ceramics and textiles and contemporary media such every bit video and performance art. Involvement in not-Western art increased, accelerating dramatically in recent years.

Queen Mother Pendant Mask (Iyoba), 16th century, Edo peoples, Court of Benin, Nigeria, ivory, atomic number 26, copper, 23.viii 10 12.7 x 8.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC Past-NC-SA 2.0)

Today, the biggest social evolution facing art history is globalism. As our world becomes increasingly interconnected, familiarity with dissimilar cultures and facility with diversity are essential. Art history, equally the story of exceptional artifacts from a broad range of cultures, has a part to play in developing these skills. Now art historians ponder and argue how to reconcile the bailiwick'south European intellectual origins and its problematic colonialist legacy with gimmicky multiculturalism and how to write art history in a global era.

Smarthistory's videos and manufactures reflect this history of art history. Since the site was originally created to support a class in Western art and history, the content initially focused on the most historic works of the Western canon. With the primal periods and civilizations of this tradition now well-represented and a growing number of scholars contributing, the range of objects and topics has increased in contempo years. Most importantly, substantial coverage of world traditions outside the Westward has been added. Every bit the site continues to aggrandize, the works and perspectives presented will evolve in step with contemporary trends in art history. In fact, equally innovators in the use of digital media and the net to create, disseminate, and interrogate art historical knowledge, Smarthistory and its users have the potential to help shape the hereafter of the field of study.

Cite this folio equally: Dr. Robert Drinking glass, "What is art history and where is information technology going?," in Smarthistory, Oct 28, 2017, accessed May 7, 2022, https://smarthistory.org/what-is-art-history/.

Source: https://smarthistory.org/what-is-art-history/

0 Response to "Is There a Humanist Style of Art Through History"

Post a Comment